What is a greedoid?

Greedoids pt. 1

Mar 23, 2022 • Garrett Tetrault • 10minGreedy algorithms build up a solution by making the locally optimal, or "greedy", choice at each step. For certain problems, this family of algorithms produces optimal solutions. Other times, using a greedy algorithm can return woefully incorrect results. So, when can a greedy algorithm be used to find the optimal solution?

Greedoids, a mathematical construct in combinatorics, help shed light on this question. In fact, it's right there in the name! Greed- as in "greedy algorithm" and -oid as in "resembling" or "like". Formulated 1981 in by Bernhard Korte and László Lovász, greedoids provide a useful framework for thinking about optimization. They make explicit the common properties that allow problems to be optimized by the simple "greedy choice" procedure.

In this post, the concept of a greedoid will be introduced and the intuition behind it will be developed. To that end, we will work backwards from a greedy algorithm and build up to an accessible definition of a greedoid.

Kruskal's algorithm

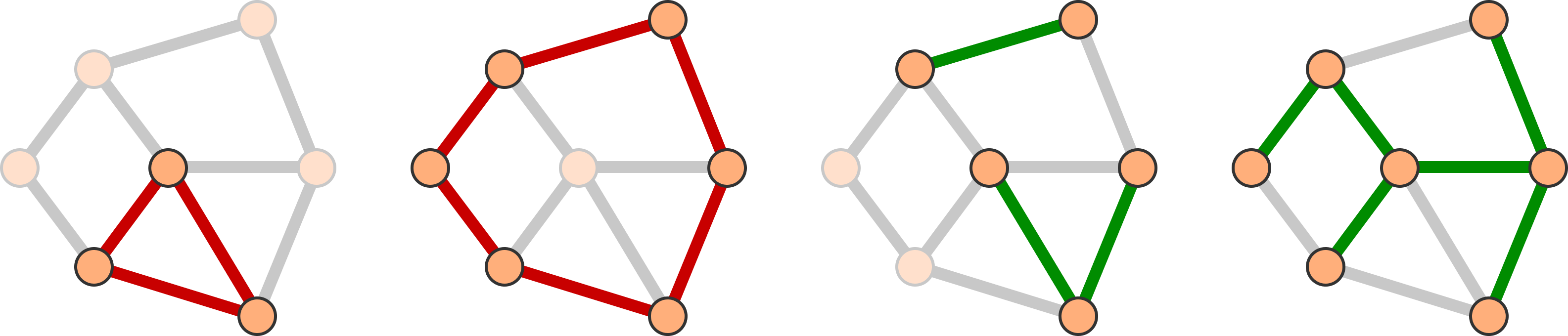

Kruskal's algorithm, which solves the minimum spanning tree (MST) problem, makes for a good case study. In this problem, each edge in a connected graph is given a weight and we are tasked with finding the set of edges that form an MST.

At a high level, Kruskal's algorithm starts with an empty set and repeatedly appends the cheapest edge that doesn't create a cycle. The core of the algorithm is translated into Python pseudo-code below:

def kruskal(graph, weight_fn):

# Python set object that can be added to by the union operator "|".

solution = set()

for edge in sorted(graph.edges, key=weight_fn):

candidate = solution | set(edge)

if not contains_cycle(candidate):

solution = candidate

return solution

What can be drawn from this?

One observation is that the edges of graph make up the search space of our problem; this establishes a domain for our optimization.

A second observation is that, despite its name, the variable solution only makes up an MST (a proper solution for this problem) when it is being returned.

At every other point along the way, it is only a "partial solution".

Additional observations about these partial solutions can be made:

- The initial condition

solution = {}means that the empty set is a partial solution. - The

not contains_cyclecondition ensures that every partial solution is a forest.

A forest is a graph that contains no cycles. The name comes from the fact that a forest looks like many disconnected trees. These separate trees are called the components of the forest.

From these observations, we have that the solution is an MST while the partial solutions are the collection of all sub-forests of graph.

In a more general sense, a solution is what the algorithm is optimizing for, while the partial solutions are the snapshots at each iteration.

The building blocks

These ideas of search space, solutions, and partial solutions are the building blocks of a greedoid. In greedoid theory, the search space is referred to as the ground set, solutions are called bases (plural of basis), and the collection of both the solutions and partial solutions are known as the feasible sets.

Of note is that the above observations are not specific to just the optimal solution. This means that the notion of partial solutions extends to all possible solutions for the problem. Indeed, the feasible sets of a greedoid capture all such solutions and partial solutions.

For Kruskal's algorithm and the MST problem, these sets would have the following form:

- The ground set consists of the edges of the given graph.

- The bases are the collection of all spanning trees.

- The feasible sets are the collection of all (not necessarily spanning) forests.

Notice how the feasible sets naturally contain all bases.

Having a ground set and feasible sets alone does not make a problem a greedoid. Indeed, most problems can be be put into the framework of ground set (domain) and feasible sets (constraints). But, these building blocks provide a language to describe the properties needed to ensure the optimality of a greedy algorithm.

The defining properties

Uncovering these requisite properties is no small feat. One has to:

- Identify properties that capture the features a greedy algorithm exploits.

- Determine if these properties generalize well.

- Ensure that these properties can be formalized (in a manageable way), so proofs and assurances can be made.

This is where the insights Korte and Lovász come in. They noticed two properties, accessibility and exchangeability, that effectively satisfy these conditions.

Accessible set systems

Consider the following procedure in the context of the MST problem:

- Hand pick an MST within

graph. - Record the edges of this MST into the set

hand_picked. - For each edge, assign

hp_weight_fnto zero if inhand_pickedand one if not. - Run Kruskal's algorithm with inputs

graphand the functionhp_weight_fn.

Under these circumstances, Kruskal's algorithm would return back exactly the set hand_picked.

Because hand_picked is arbitrary, any MST could be chosen to construct this set.

As such, every basis must be reachable from our starting point, the empty set.

The above procedure can be repeated with "forest" in place of "MST" in step one.

In this case, if the hand-picked forest has $$n$$ edges,

then the first $$n$$ elements of the output of Kruskal's algorithm would be hand_picked.

This implies that the hand-picked forest was visited during some iteration.

This widens the previous statement to the following: every feasible set must be reachable from the empty set. This is the essence of accessibility.

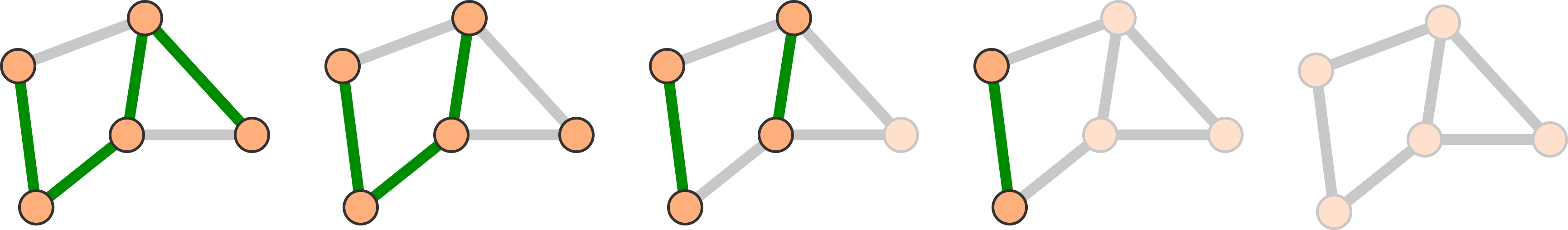

To illustrate how this is formalized, consider the partial solutions leading up to hand_picked.

For Kruskal's algorithm to arrive at hand_picked, is must have added an edge to a forest one with one less edge.

The same applies to this smaller forest.

Repeating this yields a chain of smaller and smaller forests.

Eventually, the empty set (the starting point for Kruskal's algorithm) will be met.

This chain can be traversed in reverse order such that, from the empty set, we can iteratively append edges to arrive at hand_picked.

If we swap "forest" for "feasible set" in the above, we get a similar chain that starts from the empty set and ends at an arbitrary feasible set. This chain can be similarly traversed; this is what is meant by "reaching" a feasible set.

Formalizing the existence of this chain yields the following definition: a collection of feasible sets is an accessible set system if every feasible set contains a feasible set one element smaller.

The exchange property

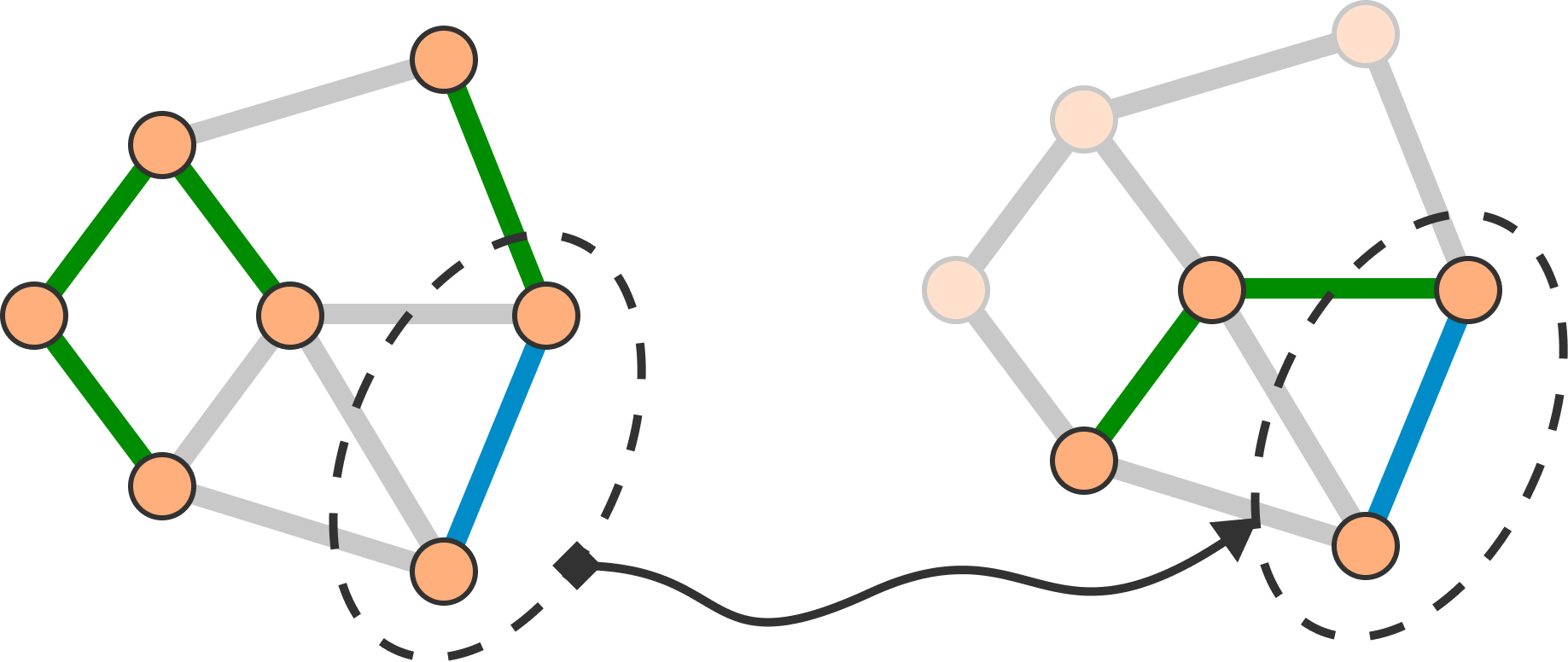

This brings us to the exchange property. Here the concern is another requirement of a greedy algorithm: a basis must always be returned. For example, a greedy algorithm for the MST problem must always return a spanning tree (dropping the "minimal" requirement for the moment). Equivalently, the greedy choice must never lead to a dead-end.

A dead-end occurs when an algorithm is iteratively constructing a basis, but reaches a non-maximal feasible set and cannot move forward. That is, when no elements in the search space can be appended to make a larger feasible set.

So, the opposite of a dead-end is the ability to append to non-maximal feasible sets. Because bases are maximal feasible sets, growing feasible sets always ends up at a basis. This reasoning allows us to reduce the requirement "a basis must always be returned" to "we must always be able to append to non-maximal feasible sets".

This reduced statement is still too hazy to be formal. To resolve this, Korte and Lovász shifted perspective: instead of appending to a single feasible set, consider the interplay of a feasible set with all others.

To that end, the MST problem will again be probed.

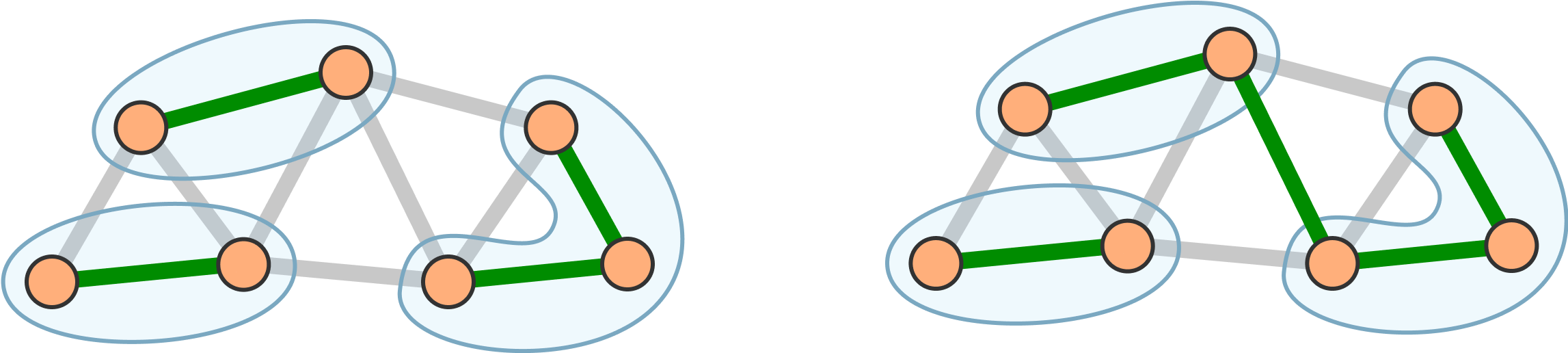

Let smaller and larger be forests with the latter containing more edges.

The goal is to find an edge in larger that can be appended to smaller.

Comparing the nodes in each set, there are two cases:

- The set of nodes in

largerhas at least one node not insmaller. - All nodes of

largerare also insmaller.

In the former case, any edge containing a node not in smaller can be chosen.

This would create a branch off of smaller into new territory (the new node).

In the latter case, consider the components of each forest.

Because larger has more edges, it must have fewer components.

If not, then one component would contain a cycle.

By the pigeonhole principle,

there must be two or more nodes that are in different components of smaller,

but are in the same component of larger.

Along the path between these nodes, there is an edge that spans components of smaller.

Because it spans components, this edge can be added without creating a cycle.

This shows that for any two forests, one smaller and one larger, there is an edge of the larger that can be appended to the smaller without creating a cycle.

Generalizing to greedoids gives the following: for any two feasible sets, one smaller and one larger, there is an element of the larger that can be appended to the smaller that preserves feasibility. This is exactly the definition of the exchange property.

Reversing the reduction above, this property gives the guarantee that a basis is always returned. And, though the example here relies on graph specific features, the property is remarkably ubiquitous.

Conclusion

Summarizing the results, the definition of a greedoid can now be made. A greedoid over a ground set is a collection of feasible sets that satisfy the following:

- Every (non-empty) feasible set contains a feasible set one element smaller.

- For any two feasible sets, one smaller and one larger, there is an element of the larger that can be appended to the smaller that preserves feasibility.

In the context of a greedy algorithm, what makes a greedoid interesting is that these properties ensure (respectively) that:

- Every solution can be reached.

- A solution is always returned.

And these allow a greedy algorithm work. Moreover, the properties of a greedoid are incredibly general. A considerable number of problems solved by greedy algorithms, from the MST, to Dijkstra's algorithm, to even Gaussian elimination, can be put into the context of greedoids.

However, there still are problems solved by greedy algorithms that do not have a greedoid representation. One well known example is Huffman coding.

In the next post, the capabilities and limitations of greedoids will be explored further. To that end, objective functions will be discussed and used to develop a generic greedy algorithm for greedoids. The aim is to give a picture of when one can use greedoids and how one would do so.

Thanks for reading!

References

- Björner, Anders; Ziegler, Günter M. (1992), "Introduction to greedoids"

- Boyd, Andrew E.; Faigle, Ulrich (1990), "An algorithmic characterization of antimatroids"

- Cook, William R.; Nedunuri, Srinivas; Smith Douglas R. Cook, William R. (2010), "A Class of Greedy Algorithms and Its Relation to Greedoids"

- Darío G, "Proof of Graphic Matroids (Using Rank in Context of Graph Theory)", StackExchange