Structure vs. objective

Greedoids pt. 2

May 14, 2022 • Garrett Tetrault • 8minThis is part two in a series on greedoids. In part one, we built up what a greedoid was and introduced terminology such as ground set, basis, and feasible set.

In that post, the minimum spanning tree (MST) problem was explored at length. Despite being central to the problem, we were largely able to avoid discussing the “minimality” goal. Instead, we focussed on the patterns and makeup of the spanning trees.

This exemplifies why greedoids can help in understanding greedy algorithms. They enable us to reason about a problem's structure separate from its objective.

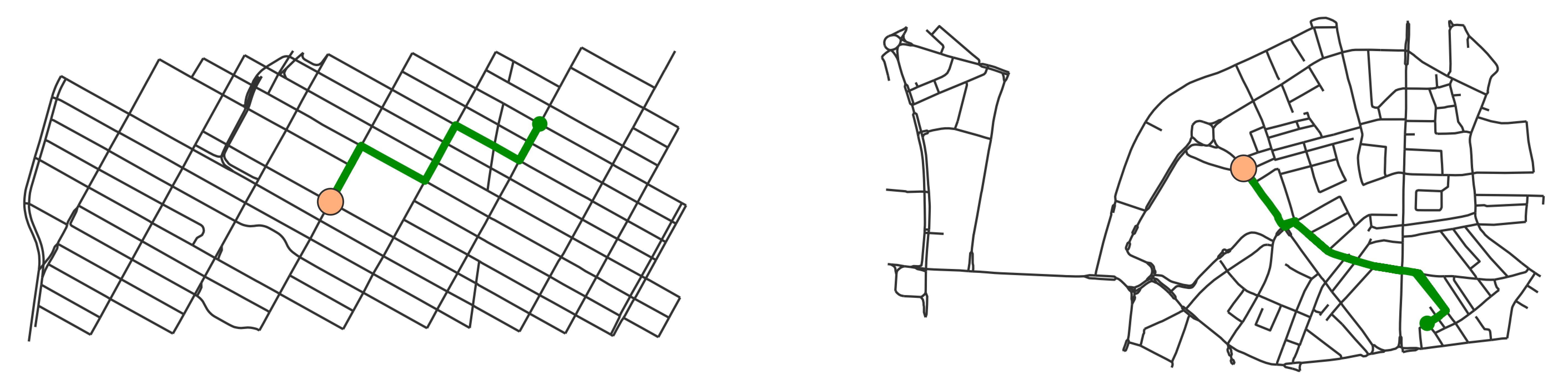

To expand on this, take the following analogy. You're in a city for a day. During you're visit, you could try to see every museum, go to dinner then a movie, or, if you're in a rush, head right for the train. These are all possible objectives for your visit. The structure is knowing how all the roads connect. If you know that the roads form a grid, mapping out you're trip efficiently is much easier.

Knowing a problem is a greedoid is like knowing that streets are organized in a grid. Just like how visiting every museums might not be possible in a day, some objectives are not optimally solved by greedy algorithms, even if the greedoid properties hold.

With the structure of greedoids covered in part one, it's time to tackle objectives. We will start by pinning down objectives and putting them in a form we can use. Then, to understand which objectives are optimally solved by greedy algorithms, a generic greedy algorithm will be developed. Finally, a description of these compatible objectives will be given.

Objective functions

In optimization, an objective is the desired solution to a problem. For example, "the shortest route to the train station" is an objective in the analogy above.

In greedy algorithms, though, local choices are made before reaching a solution. Because of this, we need the ability to compare possible interim steps, or partial solutions, against one another. This is accomplished for greedoids by defining an objective function. Objective functions map the feasible sets, the set of solutions and partial solutions, to real numbers.

In the MST problem, the objective is a minimal spanning tree when compared by the sum of edge weights. The objective function extends this, mapping each forest (i.e. feasible sets) to its total edge weight. Below is this objective function in Python pseudo-code:

def mst_objective_fn(forest):

total_weight = 0

for edge in forest:

total_weight += edge.weight

return total_weight

This is known as a linear objective function and can be generalized to greedoids by swapping forest for feasible_set and edge for elem, as in set element.

Objectives functions are also independent of the structure of the problem. Instead of the MST, we could ask for the spanning tree that minimizes maximal degree. This is known as the minimum degree spanning tree (MDST) problem. In this case, the objective function computes the maximum degree in each forest.

Objective functions can have an interpretation across greedoids (as in weighted elements) or use problem specific information (as in node degree). In general, they can be arbitrary and represent any quantifiable goal we have in mind.

The greedy algorithm

Before seeing which objective functions can be used with which greedoids, it helps to first understand how they will be used. To that end, we will construct a generic greedy algorithm to see where objective functions fit in.

To start, greedy algorithms are characterized by the heuristic of locally optimal choices. These local choices create a path through the search space, resulting in a solution. In combinatorial problems, this path often starts at the empty set and builds up to a solution by iteratively adding elements. This is the strategy adopted here.

As with all optimization problems, the solution must also meet some constraints. For greedoids, this means that all partial solutions and solutions must be feasible sets. As such, only feasible sets are considered for the next possible value of the interim solution.

This also helps clears up what is meant by "locally optimal" for greedoids. As each iteration should minimize the next value of the interim solution, the locally optimal choice is an element of the search space that, together with the interim solution, both is a feasible set and minimizes the objective function.

As for stopping conditions, we’ll put maximal feasible sets, or bases (plural of basis), to use. These sets occur when no element of the search space can be added to a feasible set to result in a larger feasible set. Bases were introduced in the previous post as an analog to solutions, so they're a natural choice for results. So, we can keep adding elements until a basis is reached.

And that's all we need! To make this more concrete, the procedure and conditions above are expressed in pseudo-code below:

def greedy_algorithm(greedoid, objective_fn):

# Python set object that can be added to by the union operator "|".

solution = set()

while solution not in greedoid.bases:

# Search for the locally optimal choice.

min_elem = None

min_val = inf

for elem in greedoid.ground_set:

# Only elements that form feasible sets with the interim

# solution are considered for next possible steps.

candidate = solution | set(elem)

if candidate in greedoid.feasible_sets:

# Use objective function to compare candidate solutions.

val = objective_fn(candidate)

if val < min_val:

min_elem = elem

min_val = val

# Update interim solution.

solution = solution | set(min_elem)

return solution

Compatibility

Coming back to the MST and MDST problems; despite working on the same spanning trees, the two problems have markedly different complexity. The MST problem can be solved by a simple greedy algorithm, while the MDST problem is NP-hard. It cannot be solved optimally by any greedy algorithm.

This illustrates compatibility. If an objective function is compatible with a greedoid, then a greedy algorithm finds an optimal solution. It is worth noting that compatibility is defined for a pair, one greedoid and one objective function. While there are objective functions compatible with all greedoids, in general it is a pair-specific property.

Th definition of compatibility comes from the following observation.

Consider a greedoid and compatible objective function in greedy_algorithm.

Because they are compatible, an optimal result will be returned.

Knowing this, at a given iteration there is no need to consider future steps; the greedy choice provides a path to an optimal solution.

Said another way, if min_elem is the best local choice, it ought to be picked as there is nothing to gain from waiting.

This implies that not adding min_elem to solution won't open up better options in the future; it will be the best choice until it is picked.

That is, if min_elem is the locally optimal choice at a given step, then min_elem is locally optimal at every later step (if not previously chosen).

This is the crux of compatibility.

This can be formalized by expanding the definition of locally optimal, then replacing the pieces that refer to the greedy algorithm with arbitrary sets and elements. For example, "interim solution" can be replaced with "all feasible sets", and so on like this. This definition is more apt to proofs, but the statement above captures the same idea.

Conclusion

We now have tools to determine if a problem is optimally solved by a greedy algorithm. If the structure of a problem is a greedoid, and the objective can be represented by a compatible objective function, then the greedy algorithm works. A procedure to preform this check would look like the following:

- Identify the feasible sets and bases of a problem.

- Show that they have the greedoid properties (covered in the previous post).

- Adapt the objective into an objective function over the feasible sets.

- Show that the objective function is compatible with the greedoid.

Further, if we have a greedoid and compatible objective function, greedy_algorithm provides a readily available algorithm that gives an optimal solution.

Though some optimizing would likely need to be done, it provides a nice foundation to start from.

Greedoids enable a deeper understanding of the problems they encompass. They make explicit the common properties that allow problems to be optimized by the simple "greedy choice" procedure. Moreover, they allow for analysis of a problem's structure separate from its objective, surfacing relationships between problems.

This is the end of my series on greedoids, wrapping up a hopefully approachable introduction to an interesting subfield of combinatorics.

Further reading

For those wanting to dive deeper, I recommend taking a look at the references for this series. They provide a more rigorous treatment of greedoids, defining the ideas discussed more concretely.

A topic not talked about here, which is covered in the references, is the idea of greedoid languages.

These are formal languages that allow for the study greedy algorithms on ordered lists as opposed to unordered sets (as in greedy_algorithm).

In particular, they account for objectives functions that are order dependent, opening up new types of problems that fit into this framework.

Single machine scheduling is one such problem.

Another avenue is the related field, matroids. Matroids are a constrained subset of greedoids that provided inspiration for their development and share much of the same ideas. They also draw connections between graph theory and linear algebra (among other interesting properties).

References

- Björner, Anders; Ziegler, Günter M. (1992), "Introduction to greedoids"

- Boyd, Andrew E.; Faigle, Ulrich (1990), "An algorithmic characterization of antimatroids"

- Cook, William R.; Nedunuri, Srinivas; Smith Douglas R. Cook, William R. (2010), "A Class of Greedy Algorithms and Its Relation to Greedoids"

- Habib, Michel (2016), "About Greedoids"